2. On the Way to Conceptual Paradise (2005)1)This text (2006) is based on a lecture at the conference: New Research in Conceptual art, Norwich Gallery, February 25th 2005.

Stefan Römer

1. Deconceptualizing the Conceptual art Complex

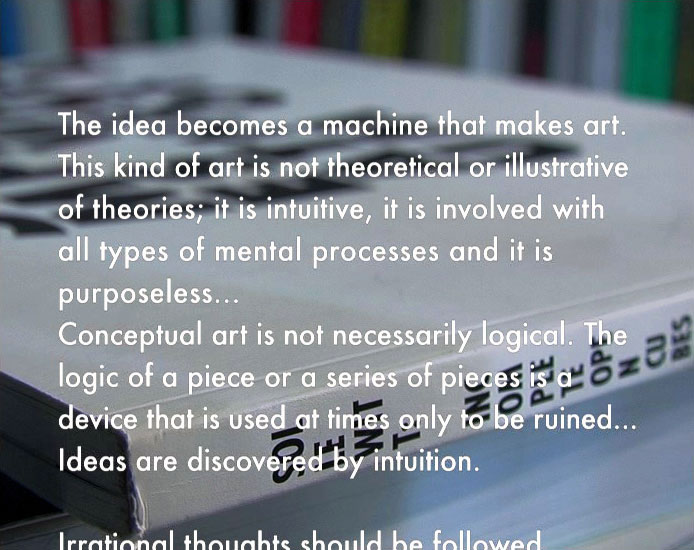

For me, writing the now historical Ism »Conceptual art« with a lower-case »a« means to constantly renew or at least keep alive the discussion about this set of visually as well as thematically heterogeneous art practices initiated in the 1960s. It also means to resist the appropriation of the attribute »conceptual« in the sense of »important« or »meaningful«, i.e. »valuable« for contemporary art practices, as it is used rather inflationary in press releases and art criticism. In this movement, at issue for me is the distinction (particularly pertinent in German) between a »conception«, which can lie at the basis of every kind of artistic work, and a »conceptual« practice, which strives toward and visualizes a level that engages media, institutional, and/or epistemological elements. In this context it is irrelevant to which of the three production processes named by Lawrence Weiner this applies.

Since the end of the 1980s the practices of Conceptual art have served as a background for my reflections. My own artistic interest to develop an art that combines––in Daniel Buren’s sense––practice as the »taking account of existence« and theory as the »precise cognition of these problems«2)See Daniel Buren, Achtung!, in: Daniel Buren, Achtung! Texte 1967-1991 (Attention! Texts 1967-1991), Ed. by Gerti Fietzek and Gudrun Inboden, Dresden and Basel, p. 82f., is based on my reception of the works of Conceptual art as a relation between image and text. I call this combination of practical and theoretical work »deconceptual art practice«, with which I bring poststructuralist considerations into productive confrontation with contemporary (post-) conceptual art.3)See Stefan Römer, Dekonzeptuelles Coding und Software Art als künstlerische Strategie sozialer Auseinandersetzung (Deconceptual Coding and Software Art as an Artistic Strategy of Social Examination), see: Franz Liebl and Thomas Düllo (Ed.), Cultural Hacking. Kunst des strategischen Handelns (Cultural Hacking. The Art of strategic Action), Vienna 2005, p. 102-121Beyond the surface, the visuality of some contemporary art practices has partly become retro-stylized display, also due to the fact that command of the market then as now quite clearly prefers saleable material objects to theoretical reflection. But exactly to criticise this mode was a central impulse behind Conceptual art. 4)In Seth Siegelaub’s words: »All of whom perhaps could be characterised by their desires for moving out of the traditional confines of the gallery or the art world structures.« Interview with Seth Siegelaub, Catherine Moseley, in: Conception. Conceptual Documents 1962 To 1972, Norwich Gallery, Norwich 2001, p. 147. In the catalogue “Conception” published by the Norwich Gallery Seth Siegelaub differentiated between »primary« and »secondary information« 5)Ibid. and ibid., p. 146., and saw the book as a more ideal and favourable exhibition space than the gallery.

Here, since the 1970s two fundamental shifts of the concept of art can be registered: the original character of art tends to become a fake––or more precisely, a combination of original and forgery––and the presentation space of the White cube has become an atmosphere, a saleable feel – what I call the Ambient. This has far-reaching consequences for the concept of art and its sub-categories such as the artistic subject/self, pictorial representation and the concept of production and reception. While the White Cube was dominated by the paradigm of the ideal presentation of paintings and sculptures as well as the »radical« gesture of violating this paradigm, now this Ambient corresponds to interdisciplinary and multimedia art programs of entertainment which operate with an extended concept of visual (cultural) presentation. These re-evaluations and shifts are closely related to different practices of Conceptual art. However, Conceptual art in this context is not understood as a clearly defined artistic genre that would be equivalent to an “ism”, but an art discussion that constantly re-designs and updates itself precisely by participating in it.

In this framework I explore Conceptual art in this film as constructions of discourses contingent upon particular contexts. In contrast to this premise, the interest in constructing a hegemonic history appears to be a form of market labelling – for example the question of who did what first, as it turns up in the film. Instead, I am interested in discussing various kinds of positions with regard to the contemporary visual culture of the Ambient. My film is conceived as artistic practice of the participation in a discourse, that formulates practice, theory and history. In so doing, in each case the medium (of visualization or discussion) chosen is a strategic artistic decision.

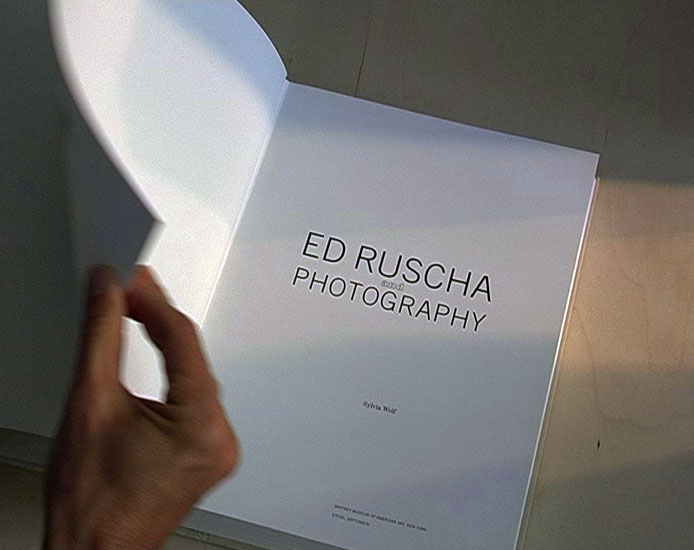

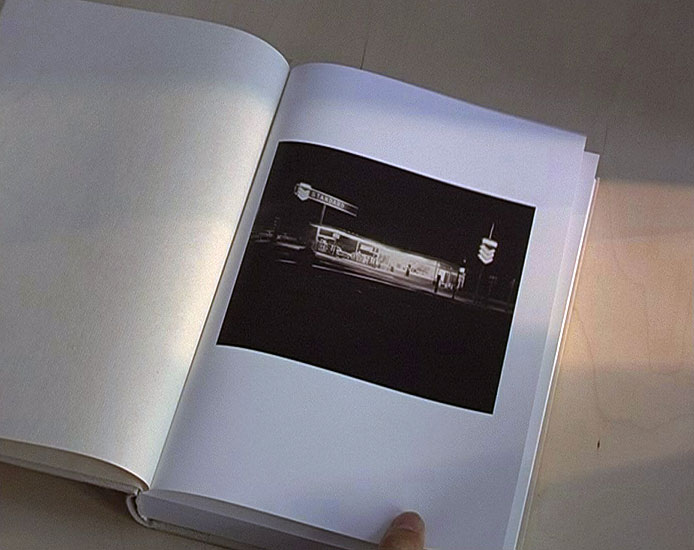

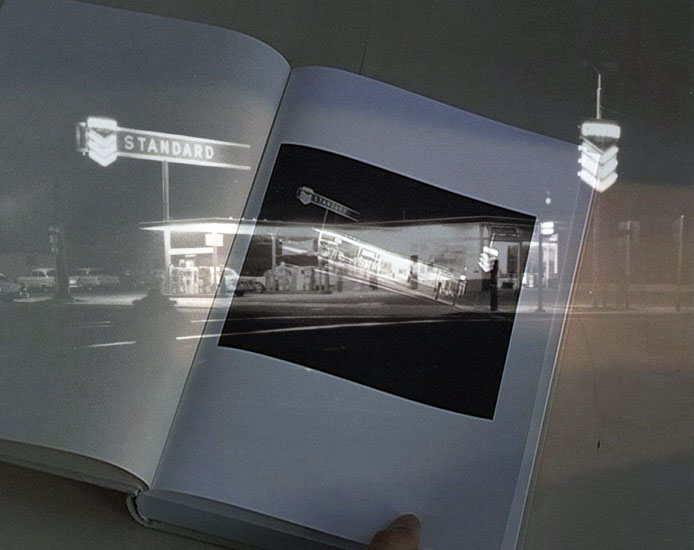

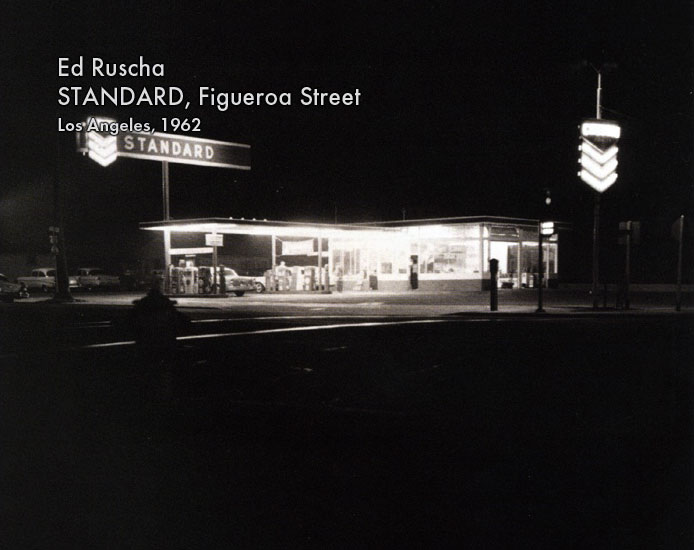

As far as my own visual socialisation is concerned primarily filmic images of artistic appropriation of reproduction forms (and vice versa) play an important role – be it a persiflage in a film by Rainer Werner Faßbinder or be it the anti-hierarchical images in the work of John Baldessari or Ed Ruscha. Although film and television are considered popular media, they currently provide only very limited media extensions or transformations of the representation of art: what sells are biographies about great artist figures, eroticism, and scandals. The programming of airtimes is dominated by the fiction of television ratings and an associated populism. This is based on the rhetoric that the audience wants to see nothing but stars. Artists who rule the market are regarded as stars. Consequently mainly stars are presented that already have a dominant function.

Productions from the mid-twentieth century like Clouzot’s Picasso film, which, as part of Modernism, represented the creative individual and the emergence of his art in a very innovative way, can here be contrasted to Guy Debord’s “Against Film” (1964) or the video gallery of Gerry Schum and Ursula Wever; here, the avant-garde still was the site of visual and social experimentation which already pointed at a new formation of the artistic concept of the subject.

By its polyphony alone Emile de Antonio’s legendary interview film “Painters Painting” (1972) defines a place of artistic production – in this case New York from the 1950s till the 1970s – although without engaging in a theoretical level of reflection. “Step Across the Border”, a filmic portrait of the jazz musician Fred Frith by Nicolas Humbert and Werner Penzel (1990), combines Frith’s music with long shots of travel images which are unusual on TV and trusts the poetic created by this combination. In today’s post modernity, visual experimentation serves as attention getter for Hollywood’s grand narratives, although it requires an extremely high level of visual and narrative reflection. If, however, art adheres to traditional differences like that between high culture and popular culture, in the Ambient it will be increasingly difficult for art to compete with the cultural industry, since now the standards of the latter are also applied to art: a cost-benefit calculation takes high visitor numbers as the proof of success; this in turn influences the planning and conception of exhibitions and other projects.

2. The Film Project Conceptual Paradise

As much as I would like my current film project Conceptual Paradise, which is based on 50 Interviews, to be seen as a documentary, due to its experimental make-up it equally seems a fiction, a phantasm, a story: a construct moulded by subjective realizations and experience: On the way to conceptual paradise.

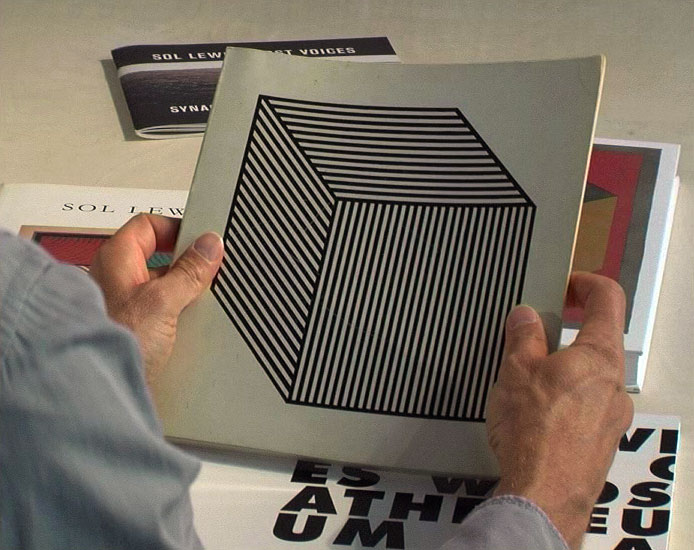

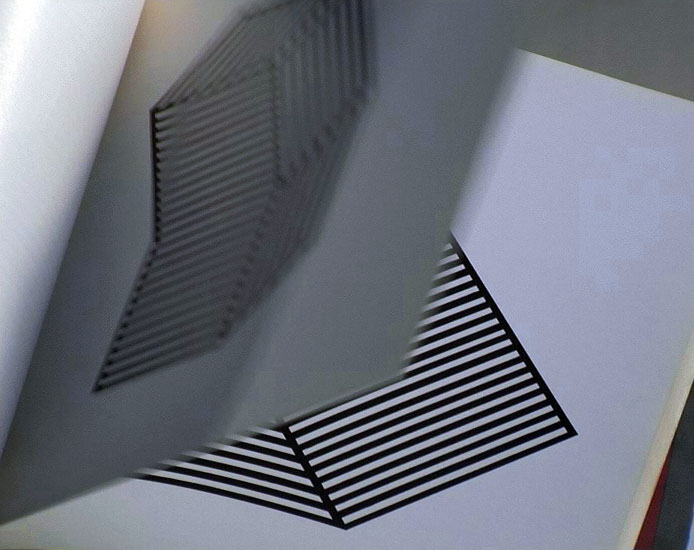

Today, Conceptual art is attributed great importance, although as a market segment it seems more or less limited and only few of those who then participated can be found among the prominent artists. While no one can deny the influence of the conceptual movement on contemporary art, it is not so easy to actually prove its traces; conceptual art was characterized from the very beginning by the debate over its historical formation or its epistemological consistency, just as well as whether it is marked by a process of dematerialization, or whether this mode of consideration is rather a misconception. For the assumption that Conceptual art is marked by dematerialization would mean that art in general is only to be completely comprehended in terms of its materialization or its form. This in turn would imply ignoring the definitional influence of art on the general symbolic system of society. Conceptual art’s epistemological break with the art tradition would then lie in the new routes taken by this discourse. But it is precisely the obvious differences of Conceptual art to other art forms beyond any style, which are difficult to name in contemporary art, that make it such an interesting – and perhaps invisible – subject for a film.

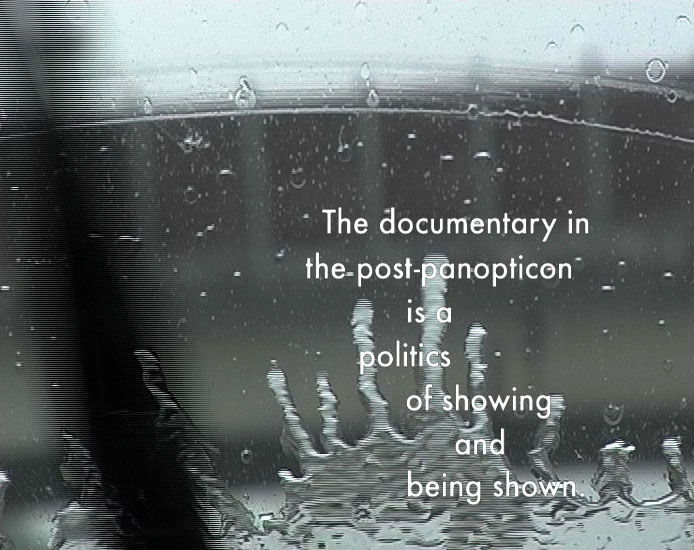

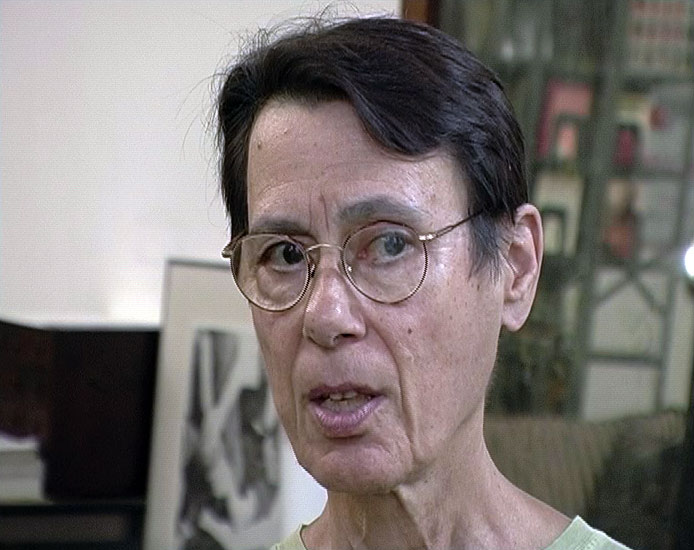

On the basis of their reflective art practice, the protagonists of this movement seem especially well suited as interview partners. But how does one show their work, without falling into the familiar practices of representation, often inappropriate for the art? Stereotypical here are TV programs that show an exhibition space while the voice of the artist can be heard off camera. In this regard a form of mythologizing traditional art history by way of illustrating the face 6)The recognition of the face equals the indexical specification of a person. Gilles Deleuzes and Felix Guattari mean, that the human disposition to recognize faces in nature and in complex structures is not a matter of »some anthropomorphism. The facial recognition is not about resemblance, but causative.« Thus Picasso’s mania for decomposing faces in most of his paintings is not to be understood as pictorial metamorphoses, but as his reluctance to allot a minor function to the face in the image. Western art seems to be strongly fixated on the face as an image: faces characterize the persons represented, whose lines of sight tell the story and direct the viewer’s gaze. Deleuze and Guattari are of the opinion that human beings do not speak a general language, »but a language, whose significant features are coordinated with their specific facial features.« But the face is not universal: »Even the face of the white man is not universal, but the ›white man‹ with his broad white cheeks and his black eye-sockets is. The face is Christ.« Deleuze and Guattari emphasise the dominance of the face in Christian iconography, and how it tends to be used in advertisements as means of identification with the actors. »If the face is a policy, then the decomposition of the face is a policy that involves actual becoming, becoming clandestine.« The Talking-head-interview is thus a part of the facial policy of our culture. and quoting a literal statement of the artist in order to achieve an allegedly original understanding of their art is a prime example. However, the reversal of this stereotype has shown Conceptual art’s critique of modernism typical since the interventions, performances and theoretical texts of the historical movement. In my film, some artists elude a personal filmic depiction: for example Valie EXPORT suggests instead to show a sequence of her film »Syntagma« and Michael Asher states: »I never know, why personal subjectivity must be placed in a representation.« This elusion of the face of the artist is contradictory to the contemporary politics of representation in the post-panopticon.

In her serial film “An Inadequate History of Conceptual Art”(American Fine Arts Gallery, New York 1999) Silvia Kolbowski tries to counter the dominant facial politics of representation by just showing the hands of her interview partners. My approach confronts these politics in a proactive way by creating thematic diagrams of the faces together with the texts.

It should be mentioned first of all that the basic structure of my film refers to numerous levels: the film intends to represent simultaneously a documentation of historical Conceptual art and a reflection about films that treat artistic questions, while at the same itself serving as an artistic position. This will be realized using various formats: documentary interviews, above all with the first generation of Conceptual art, based on a set of around five questions, are dialogically edited into one another with direct thematic references or are organized according to historical issues paralleled. This is complemented with clips that portray the practice of artists like Marcel Broodthaers or show important exhibitions along with free narrative passages.

This is visualized in a filmic diagrammatic in which the linkage of content and technique as well as anti-academicism and popular culture is translated into a look that is not directly reminiscent of Conceptual art. In the talking-head-situations the theoretical confrontation is preferred to the anecdote since the latter forms the autobiographical basis of the old art history where the personal relationship with an artist was thought to be a proof of authenticity. But the anecdote »resists the curiosity to learn something personal, while at the same time satisfying the spectator«7)Hartmut Bitomsky, Der Sturz der Fabel, der Mythos des Autors (The Downfall of the Fable, the Myth of the Author), see: Hartmut Bitomsky, Kinowahrheit, Berlin 2003, p. 107., as the German filmmaker Hartmut Bitomsky argues.

The conscious decision to not only allow one artist his word about his work but to allow a multiplicity of voices is due to my personal reservations regarding the monographic representation of a single artist. Thus, Conceptual art is shown as a versatile epistemologically critical discussion about the concept of art.

Since it does not seem sensible to me to pose the same questions to the individual artists that have already been asked in many interviews, I was interested instead how they themselves were influenced by other artistic strategies, how they refer to other methods in their artistic practice, and which communicative relations they maintain in their works to their models. Although this is for many artists a controversial question, since they do not like to talk about the issue of influence, they are asked about their models and their ideal of art. This projects a notion of how the so called originality of Conceptual art is currently defined.

On the other hand, it also is a risk, because the film itself has to answer the question in which argumentation and rhetoric the individual voices are placed. Herein lies the danger that I might myself seize a power position, that I install myself as a storyteller or alternatively place myself—or ourselves—on the pedestal of history – be it as an auteur or be it as a collective: »What gesture of historization do I represent?«

Making a film about art that itself is art requires defining the distance between art, its reception, and its reflection. Only by clarifying these distinctions is it possible to make a renewed differentiation of artistic practice. The film combines in a modular way the serially held interviews, and does not seek to achieve a monolithic, historicizing, linear narrative.

The mode adequate for such an ambitious conception is the video essay. This allows for a thematic and technological-media visuality to be developed that in turn permits various research approaches to be combined in a diagrammatic montage. The use of a diagrammatic montage of the interviews and narrative elements demonstrates the self-evident function of the medium. An artistic expression and its context are subject to a playful combination, which nonetheless in the rhetoric of the film is placed in a new context. The function in each case is a mouse click.

A film only with art stars.

The content of the documentary is completely fictitious.

The film reconstructs historical details, but the similarities with existing figures are, as always, purely coincidental.

The history of the is film based on the phantasms of the participants.

The depictions are enacted and correspond to reality.

To tell one of many stories about conceptualism.

A film is (not) a film.

This is not a film.

But Conceptual Paradise – a place for sophistication

Translation: Dr. Brian Currid and Birgit Herbst