3. On the Construction of Contemporary Polyvocality.(2008)

The Interview in the Documentary Conceptual Paradise as a Strategy of Actualization 1)This essay is based on a conference presentation (GAK, Bremen June 24-28, 2007), reprinted in: Blind Date. Zeitgenossenschaft als Herausforderung, ed. by Gabriele Mackert, Viktor Kittlausz, Winfried Pauleit, Nuremberg 2008, p. 156-163.

Stefan Römer

1. Get everything from the now

With the slogan „Make the most of now,“ a cell phone company is currently advertising the effectiveness of the now. Perhaps this refers to a contemporaneity in the sense of time spent together and a participation in or sharing of opinions in a present that can be experienced through permanent media communication with many people/contemporaries. Possibly, however, this „now“ is not reflectable due to its fleetingness, but only reflexively reconstructable on the basis of its documentation of whatever kind. How a content relates to this is a completely different.

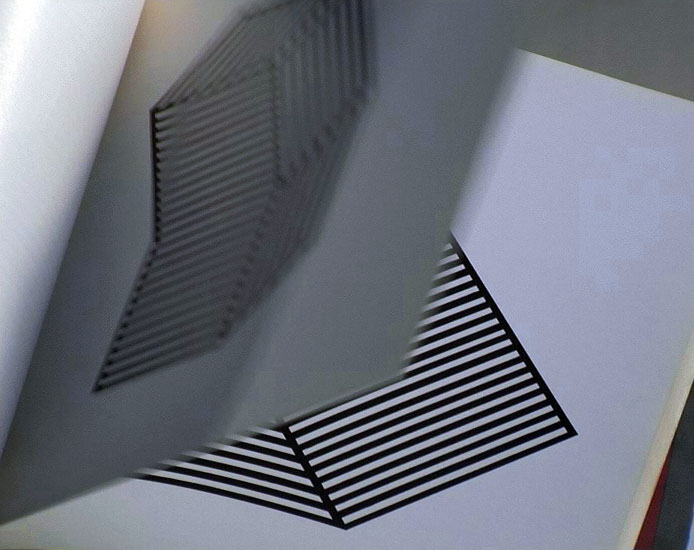

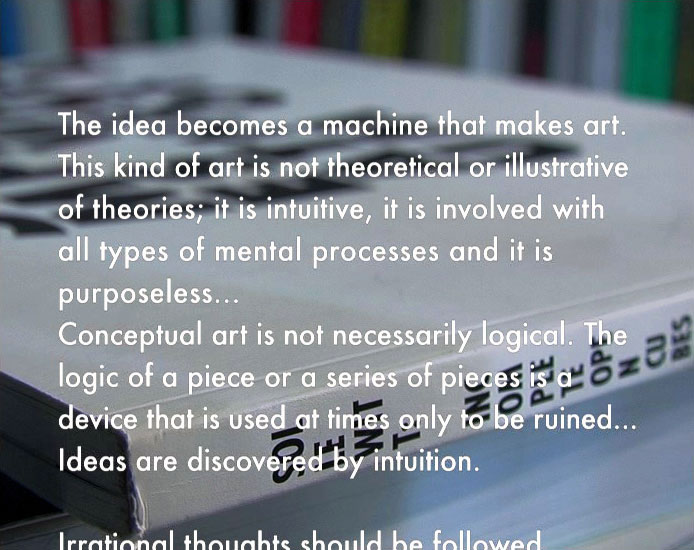

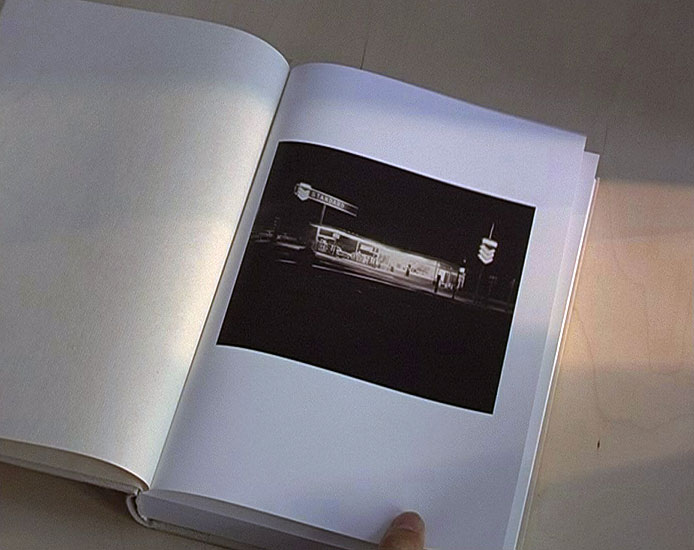

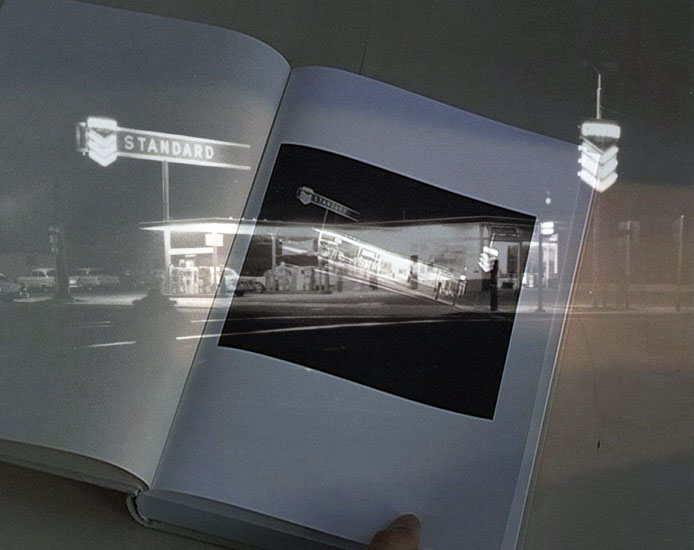

There was no concrete occasion for my documentary essay film „Conceptual Paradise“ that could have been documented. A definition of „contemporaneity“ was also far from my mind when I started working on the film. I was much more interested in understanding so-called contemporary artistic positions and tendencies that relate or can be related to Conceptual art in different ways. At the same time, I was interested in updating conceptual approaches and questions for contemporary art practice. A decisive prerequisite for my documentary „Conceptual Paradise“ was the observation that in and after the 1990s a multitude of visual or presentation-related references to Conceptual art could be found in contemporary art. What seemed significant to me, however, was that many artists associated it less with self-generated philosophical reflections or art- and epistemological-critical statements, as was typical for the first generation – e.g. the artists of the group Art & Language or, in other ways, later practices such as Martha Rosler’s or Renée Green’s. Instead, modes of representation are now often appropriated or imitated by conceptual artists. The prerequisite for this are the practices of the first Conceptual art generation, which iconically programmatically stand for a certain authorship and conception of art and became visual stereotypes. I am a big fan of the discourse of Conceptualism because I am equally interested in the visual other of Conceptual art as rigid and severe, as in the spectrum between high-end perfectionist and naively amateurish; moreover, I am impressed by its art-critical and theoretical self-empowerment that produced these particular visual representations. However, when these congeal into dogma in conceptual practices, it also reveals precisely the problematic nature of their discourse.

At the same time, the discussions around Conceptual art seemed to reverberate in press releases in which the terms „conceptual“ or even „conceptional“ (German: „konzeptionell“) were invoked as value producers, instead of striving for an actualization of conceptual questions – or subjecting that advertising rhetoric to a discourse analysis.

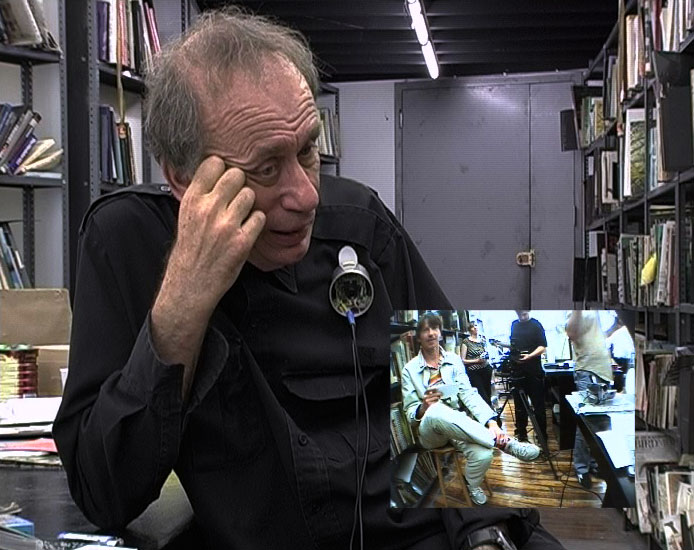

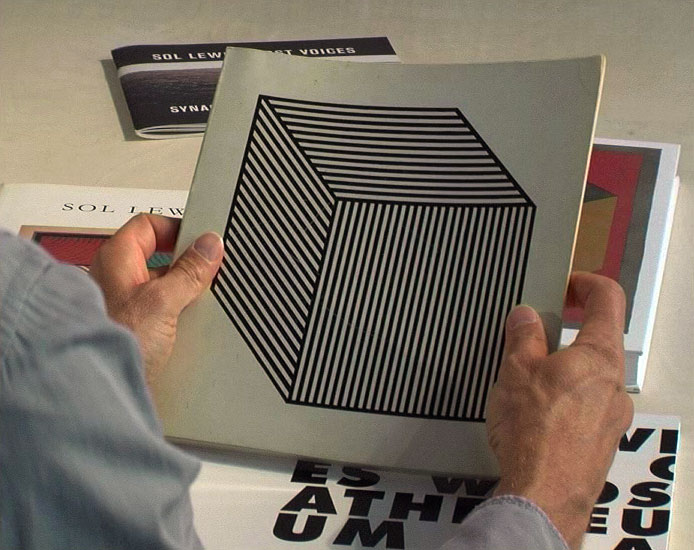

Against this background, I intended to stage a discussion with conceptual artists of different generations in a film. In doing so, my primary interest was not directed towards a historical representation; however, this had to be considered as a side effect. Therefore, I made certain choices for historical references; for example, the conceptualist Sol LeWitt, who is important in my understanding, presents a sketch for the interview in which he derives a genealogy of Conceptual art from Russian Constructivism, while in parallel he relates Pop art to Marcel Duchamp, Dada, and Surrealism. This is immediately followed in the film by Dan Graham, who emphasizes the importance of LeWitt for his own practice, but at the same time sketches out a completely different genealogy. Thus, it is clear from the very beginning of the film that it is a matter of staging a discussion – not of believing in a single, all-valid definition. This is what the essay film – the most contemporary of all media – allows me to do. This film is artistic practice and theory. I didn’t want to curate an exhibition, but to conceive a media statement that, as a film and as a web archive, should open up different possibilities of reception

2. On the conception of the documentary Conceptual Paradise.

The recently deceased art critic, Harald Fricke, wrote that his contemporaries were those with whom he shared generation and thus pop-cultural fashions and their reception. To him, „comrade“ is a congenial term because it implies those with whom he spends some time in art.2)Vgl. Harald Fricke, Was Neuheit bedeutet? („What novelty means“), Internetmailinglist Berliner Gazette, 15.5.2007.

In this sense, my very personal hedonistic – dominated by Kairos – consideration at the beginning of the film project was that I would like to seek out certain personalities and discuss current art developments with them. It is also obvious that because of the age of the first generation of conceptual artists, there was a certain existential condition – dominated by Chronos – that resulted in a certain urgency to document. In addition to the art-critical observation outlined above, I refer to this personal and objective formation as the documentary impetus for this film project.3)My point is to continue the discussion that Foster precisely makes in the chapter „The Artist as Ethnographer“; cf. Hal Forster, The Return of the Real. The Avantgarde at the End of the Century, MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts etc. 1996, p. 171-203.

In this context, my critique of the contemporarily dominant forms of documentation played an important role as well. This hegemonic form of documentary historiography is represented by „docu-fiction“: among others, Oliver Stone gave a strong impulse to this with his film „JFK“ (1992). Heinrich Breloer – with his films „Todesspiel“ (Death-game) (1997) and „Die Manns – Ein Jahrhundertroman“ (2001), which were shown on German television at prime time – developed the method further: historical documentary material is suggestively dramatized with contemporary interviews and scenes are re-enacted with actors. In this culture-industrial form of documentation, the documentary in general loses its credibility, while at the same time establishing itself as a collective historical consciousness by turning to the large audience.

I have also made other critical reflections on the observation of the everyday subject in the docu-soap „Big Brother“ (from 2000) or the stereotypes of TV-coverage of art, as well as on the video-interviews with artists that are very widespread today. Devoid of any cinematic interest, they merely string together arbitrary interview sequences in an additive manner. As early as the 1960s, it was recognized that „documentary has replaced exposition and description.“4)Richard Roud, Jean-Marie Straub, Reihe: Cinema One, USA 1972, p. 31. This is precisely why many contemporary video documentaries seem atavistic.

Therefore, my film „Conceptual Paradise“ formulates a time-critical statement that insists on a relatively classical documentary style. I refer to the German documentary film movement around Hartmut Bitomsky, Harun Farocki, Helke Sander, who intend that the viewers should find their own way of reading the film. However, for Conceptual Paradise, their procedures were not simply adopted – for example, to avoid an illustrative relationship between image and text for ideology-critical reasons – but this relationship was adapted to the narrative situations in each case. For to blindly repeat such a tactic would mean to let it congeal into ideology itself. This approach is aimed at viewers with an emancipated receptional behavior.

3. Polyvocality instead of Monography

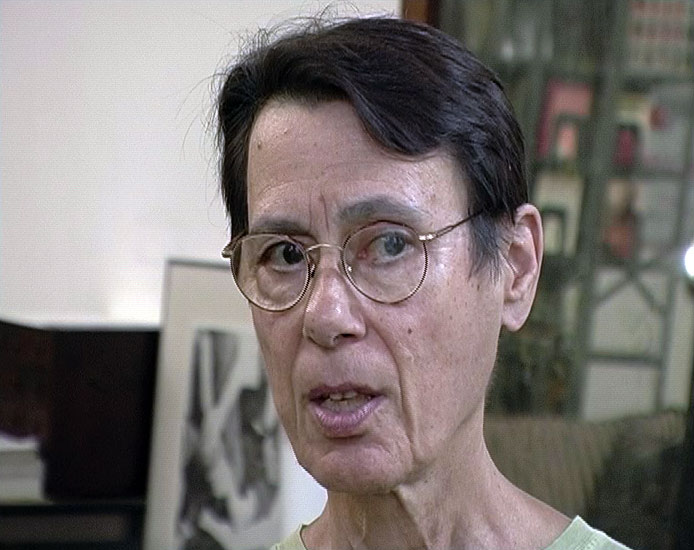

In my film Conceptual Paradise a large number of people from the art field have their say. Gathering fifty-seven different speakers in one film means that none of these people have long speaking time; some only appear with a short statement. This approach is justified by the problem that monographic representations usually lead to an individualistic idealization – if not heroization – of a single artistic personality. I regard it as a basic art historical problem that artistic achievements can supposedly only be elevated by their uniqueness, on which the modernist discourse is based. Moreover, my main interest was a discussion on the actualization of conceptual epistemological issues for this film essay.

My approach is therefore guided by the ethnologist James Clifford; he calls for „multiple authorship“ in anthropology, even if, or precisely because, in doing so, „a profound Western conviction is called into question: that the structure of any text is to be identified with the intentions of an individual author.“5)James Clifford, Über ethnographische Autorität (About ethnographic authority), in: Eberhard Berg, Martin Fuchs (Hg.), Kultur, soziale Praxis, Text. Die Krise der ethnographischen Repräsentation, Frankfurt/M. 1993, p. 147f. The notion of multiple authorship seems to be appropriate here because it suggests an authorship that sees itself as multiply read, encoded, and differentiated. This does not codify a final result, but rather stages a processual formulation. With the notion of polyvocality, I imply a documentary position that allows for different opinions as opposed to an unambiguous, doctrinaire language. My construction of this polyvocality is based on my interest in empowering viewers to form their own opinions. In doing so, however, I want to avoid a (pseudo-) pluralism, as practiced by public and private television and radio stations, which claims to let everyone have their say. For this is always only a matter of proportional representation, which offers the forces already dominant in the public sphere another opportunity for self-expression /-representation.

On the one hand, my approach of polyvocality gives the interview the function of being a document of the encounters with the respective persons and on the other hand of entering the discussion staged by the film as a fragment. My own interest in this makes me a user of the conceptual canon, insofar as I also feed my interest into this canon. I refer to the distinction between „fan“ and „user“ here in terms of different interests: As a fan, I collect enthusiastically all material I find on Conceptual art; in doing so, I act emotionally because I am pursuing a fundamental interest, while allowing for selective sympathy. As a user, on the other hand, I pursue the interest of getting involved in the discourse around Conceptual art beyond the collection of conceptual material; in this respect, my intention is also my participation in the artistic discourse. This is guided by a fundamental interest in contemporary projects.6)The term „interest“ serves as a key concept for my forms of participation in the discourse: both fan and user of Conceptual art, I have also discussed other projects in parallel since the beginning of the film project (2002); apart from the respective individual exhibitions of the protagonists, the following projects are worth mentioning: Contextualize. Zusammenhänge herstellen, Hamburg 2002; Romantischer Konzeptualismus, Nuremberg 2007; Conceptualisms, Berlin 2003; Open Systems. Rethinking c.1970, London 2005; Art after Conceptual art, Vienna 2006.

The rhetoric of polyvocality in film comes about by selecting the usable parts – i.e. after subtracting the technically and content-wise unusable takes – which is subordinated to certain dramaturgical aspects. The work of film editing can be understood as an editorial processing of the collected material: The narration of the film develops, for example, along the concepts: „irony, humor,“ „art and language,“ „body, space, mise-en-scène,“ „conceptual painting,“ „dematerialization,“ „definitions and historicization of the conceptual,“ „immaterial work“-in terms of the possibilities offered by the material at hand. The aim is to make the evidences and contradictions of the conceptual discourse as clear as possible and to include current conceptualizations as well as theories. I formulated these considerations before the film production with regard to, for example, the shooting guidelines, the relationship between theory-space mapping and the film montage, and discussed them with the film team during the production period.

4. Interest in a conceptual Now

„Every event already contains its documentation, otherwise we could not think it.“7)Jacques Derrida cites the „‚making‘ of the event“, how ways of speaking become performative: „This leads us evidently to this possibility of speaking to speak of an event, which announces itself as performative in the classical meaning: it leads us to all those ways of speaking, in which where speech does not simply mean informing, reporting, describing or ascertainment, but where it consists in letting something happen through speech.“ (Jacques Derrida, Eine gewisse unmögliche Möglichkeit, vom Ereignis zu sprechen, Berlin 2003 p. 24; translation by the author) This is based on a deconstructive reading of the concept of the event, as Jacques Derrida also applies it to the performance of the „gift“, namely that it also refers to the corresponding acts.– this is a text animation from my film. Accordingly, what is an appropriate strategy for representing the meaning of events?8)Vgl. Linda Williams, „Mirrors without Memories, History, and the New Documentary“ (Spiegel ohne Gedächtnisse. Wahrheit, Geschichte und der neue Dokumentarfilm), in: Die Gegenwart der Vergangenheit, hg. v. Eva Hohenberger u. Judith Keilbach, Berlin 2003, p. 36. And: How can I create situations in which the „action comes to me“?9)Ibid., p. 34

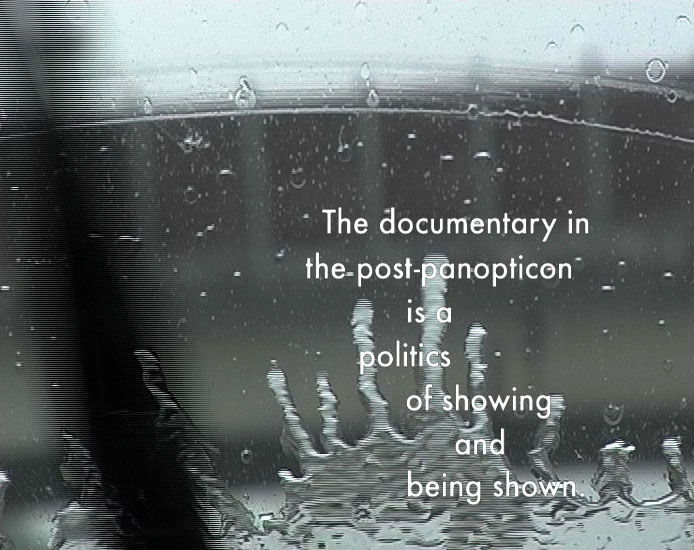

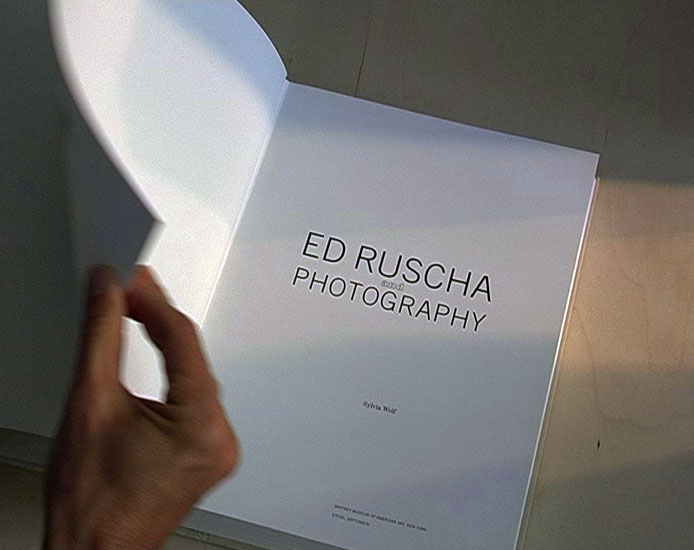

The chosen form of the film is not oriented towards any historical, conceptual aesthetics, even if it were possible to define one. I came to believe that it is precisely a research-based conceptual practice that must question the very notion of „aesthetics,“ and that at best definitions – of or interest in ideas – are the categories of Conceptual artistic thinking. Rather than reproducing a conceptual look, the visual choices in the film follow a critical reception of, among other things, Conceptual art, developing a rhetoric of the de-conceptual. To this end, specific film excerpts were repeatedly viewed and discussed with the team: from film classics such as the cartography in Michael Curtiz’s „Casablanca“ or the reflection on film economy in Jean-Luc Godard’s „Tu va bien“ to artists‘ films such as Dan Graham’s „Rock my Religion“ or Sylvia Kolbowsky’s „An Inadequate History of Conceptual Art“. In addition, there is a specific reading of Claude Lanzmann’s documentary „Shoa.“ As diverse as the aforementioned film examples appear, the specific issue is the synthesization of relevant individual elements, which in a different thematic context serve to do what Linda Williams precisely formulates for documentary film: that it should not be about representing the past, but reactivating it with images of the present.10)Vgl. Ibid., p. 37. The current theoretical conditions for the documentary are reflected in the film with the German documentary film auteur, Hartmut Bitomsky, and are also presented in text animations.

What can the interview do for this documentary? The conducted interviews form an archive from which I developed the film narrative by means of a selective process. The database that will be created later will allow for individual research in the complete interviews.

Locating the documentary sources in a film narrative means, above all, giving them a new content – the localization and context on the timeline thus generates the content of the film. The editing forms a diagrammatic montage, that is, from a plurality of possible statements, a localization of singular rhetorical elements is made with fiction, thus coming close to relative truth:11)Ibid., p. 42.

„The recourse to talking heads, to people who remember the past […] represents in these anti-vérité documentaries an attempt to overcome that conviction to realistically record ‚life as it is‘ in favor of a more intense exploration of the conditions by virtue of which it has become what it is.“12)Ibid., p. 34.

Opting for the talking-head setting of the interviews also means, first of all, creating popular access for an audience that is not educated in art theory. For the speakers, beyond their statements, form projection surfaces for a personal approach.

The contemporary self emerges through media circulation between blogs, mailing lists, talk shows, and surveillance; in the process, the personal projection of the self is valorized. A current concept of reception would have to examine this state of being permanently live: Being online simultaneously in multiple channels produces not only current forms of communication but also new social behaviors that align with the different performances of simultaneous presence.13)Cf. the chapter „Photography, Film, Truth: Inter-esse between Crisis Tableau and Online Screen.“ (Fotografie, Film, Wahrheit: Inter-esse zwischen Krisen-Tableau und Online-Screen), in: Stefan Römer, Inter-esse, Berlin 2014, p. 121-171.

In my film Conceptual Paradise, I counter this with a complex discussion between artists and theorists about the cognitive possibilities of art. A quickly thrown statement is distrusted. The focus is rather on knowledge developed through artistic practice. My artistic interest is thus reflected in the dramaturgy of narration.

In my opinion, all this can be understood as the effect of a new concept of interest – an extreme interest in the contemporary.

(Translation Stefan Römer)