4. How To Film A Documentary Without A Camera And Without Interview Partners? – Anecdotes From The Film Production

„The anecdote wards off curiosity that wants to know something personal and yet satisfies it.“1)Hartmut Bitomsky, Der Sturz der Fabel. Der Mythos des Autors („The Fall of the Fable. The Myth of the Author“), in: ders., Kinowahrheit, Texte zum Dokumentarfilm, hg. v. Ilka Schaarschmidt, Vorwerk 8, Berlin 2003, S. 107. Cf. Hartmut Bitomsky on „anecdotes and documentary“ in my interview for Conceptual Paradise.

Where is the camera?

„Why did you forget the camera in the train?“ the sheriff asks me in a low voice. Embarrassed and desperate, I reply, „I don’t know. It was a mistake.“

What the loss of the camera means for a film crew does not need to be explained. But the fact that I, as the director of the film, have to convey this to an American provincial sheriff in order to ask him for help demands something special from me.

From New York, our small film team – consisting of production manager Katja Schroeder, cameraman Andreas Menn, sound man and set photographer Martin Seck and myself – had set out on a train ride of about an hour to the Dia Art Foundation in Beacon, Upstate New York. When we got off the train in Beacon, I noticed that the camera bag was missing. So the camera was lost on a train traveling along the Hudson River.

It flashed through my mind: since we were shooting on Mini-DV with the European PAL standard, it would be difficult to find replacements because only cameras with the NTSC system were used in the U.S. at the time. Therefore, I feared a delay in filming in New York. This would put us under a lot of time pressure, because we had several shooting and interview dates planned for each day.

Fortunately, however, the sheriff was able to call the train conductor. After finding the camera, he handed it over to the stationmaster at the next station, so that the next train in the direction of Beacon brought it back after several hours. By now, however, it was too late to shoot at the Dia Art Foundation. In this way, we had made an exciting day trip, but brought back no usable footage.

Actually, I wanted to film the works of Hanne Darboven at the Dia Art Foundation. With her reduced and strictly serial works, she marked a special position in early European Conceptualism. I even managed to talk to Darboven on the phone. This required a set ritual: the gallery owner had asked me to call her on a certain day between 9 and 11:00 a.m. The phone call was very short (9/16/2005, at 10:11): after explaining my film and archive project Conceptual Paradise in two sentences, I confirmed my knowledge that she had been refusing interviews since the early 1970s. My telephone transcript reflects our conversation:

Hanne Darboven: What do you want?

SR: I know you don’t actually give interviews. But would you be interested in giving a short interview for my film Conceptual Paradise?

Through the analog phone, I heard her take a deep drag on a cigarette.

HD: I don’t give interviews anymore.

SR: Do you see any other way to participate in my film?

HD: No, not either.

SR: Are you interested in contributing to the film in any other way? I could make a conceptual video clip according to your specifications – in the sense of your – serial way of working.

After another deep drag on the cigarette, she declined my offer and hung up without saying goodbye.

An oral history requires the willingness of the actors and a recording medium. Thus, Hanne Darboven exemplifies a double failure of my film project: the artist in question refuses an interview. When I want to document her work and stage it on film, the camera gets lost.

This anecdote also has a gender aspect, because Darboven’s failure reduced the number of women artists in the project. Because, as Adrian Piper noted in the discussion following the 2006 performance of Conceptual Paradise in Berlin, there had unfortunately been very few female artists in the Conceptualism movement. The absence of Darboven’s voice meant a gap for my idea of polyvocality that could not be closed.

How can you make a film without a camera and without interviewees?

Other artists are also known for not giving interviews on principle, such as Stanley Brouwn, who did not even respond to my written request. But I was able to arrange a meeting with On Kawara in New York (2005) and he agreed that I would have a conversation with him; this conversation situation would be photographed by my team and I intended to write down his remarks later from memory and have them spoken as off-commentary on the photographs of our conversation in the film. In this way, I wanted to create an interesting video insert. But then On Kawara became ill and we could not meet.

I was also not able to meet Ian Wallace, who is considered as the father of conceptual artists such as Jeff Wall, Rodney Graham or, for example, Stan Douglas from Vancouver. For one, my travel budget was not sufficient to fly to Vancouver with the team. And he did not come to Europe during the research period; but since his recognition increased so much from 2006 onward he was invited to Europe more often and we met several times after completion of the film.

The polyvocality I am striving for (cf. in this archive my text: On the Construction of Contemporary Polyvocality. The Interview in the Documentary Conceptual Paradise as a Strategy of Actualization, 2008) also reaches its limits when the subjects are already deceased, as in the case of Marcel Broodthaers and Robert Smithson. Or when potential interview partners live too remotely to meet, as in the case of Lucy Lippard and Bruce Nauman. As a compensation I created filmic inserts that explore an artistic theme of the respective person. From Lippard, I integrated quotes as text animations. In this way, her statements made their way into the film without me meeting her in person.

So I came to terms with the fact that failures are also part of such a long and research-intensive project: Mary Kelley was traveling in Europe while we were filming in the U.S., so I couldn’t meet her. Mike Kelley, like Rodney Graham, didn’t have time. Gerhard Richter and Rosemarie Trockel canceled, while Louise Lawler had no time because her studio had just been robbed. I was able to speak to and film Jeff Wall at a lecture in Cologne’s Museum Ludwig, but he did not give me an interview due to time constraints. When he signed his book of collected writings for me after our informal conversation, a lady had her forearm signed immediately afterwards. I understood then that conceptual artists can also be pop stars.

In my understanding, Barbara Kruger is also a pop star. Her art practice, similar to Jeff Wall’s, has unfolded since 1980 around a single good idea: the respective strategic appropriation of media images, which she provides with a linguistic „mock cliché,“ that is, an imitated or appropriated quotation. Because of her reflexive approach to images and language, I expected a critical statement about conceptualism. I met her in the Munich branch of the Sprüth Magers gallery in order to win her over for my interview project. But she denied any interest in the subject and said that she had absolutely nothing to do with the Conceptual art context in the USA, i.e. she worked with other galleries and collectors. The two gallery owners present, Philomene Magers and Monika Sprüth, confirmed this with a silent nod. This institutional mindset that an art practice is defined by its relationships to collections and galleries rather than content and theory was very foreign to me.

This incompleteness of my interview project – due to death, inaccessibility, or disinterest – led me to a dialectical film structure: at the beginning of the film, the people involved are introduced under „starring,“ while a „missing“ list at the end inscribes the people who were not involved but were desired. Thus, the missing list of about sixty names commented on the implicit inclusion and exclusion process of the project. From today’s perspective, I would include more artists.

One person whose opinion about the conceptual movement was very important to me, was film director Kathryn Bigelow. But, like all famous people in LA, she could only be contacted by means of difficult procedures. In her time as a student in London, Bigelow had already written texts for „Art-Language The Journal of conceptual art“ by the artist collective Art & Language, whose members Michael Baldwin, Mel Ramsden and Charles Harrison I interviewed for Conceptual Paradise. During her time in New York she made several films for Lawrence Weiner. Later, in Hollywood, she established a reputation with feature films such as „Point Break“ (1991) and „Strange Days“ (1999), and eventually became the first female director to win an Oscar with the film „The Hurt Locker“ (2008). To get in touch with her, you had to keep in mind that you can contact people in the Hollywood inner circle only via gatekeepers.2)Cf. the function of „knowing-who“ in artistic thinking: Stefan Römer, Inter-esse, Berlin 2014, p. 164.

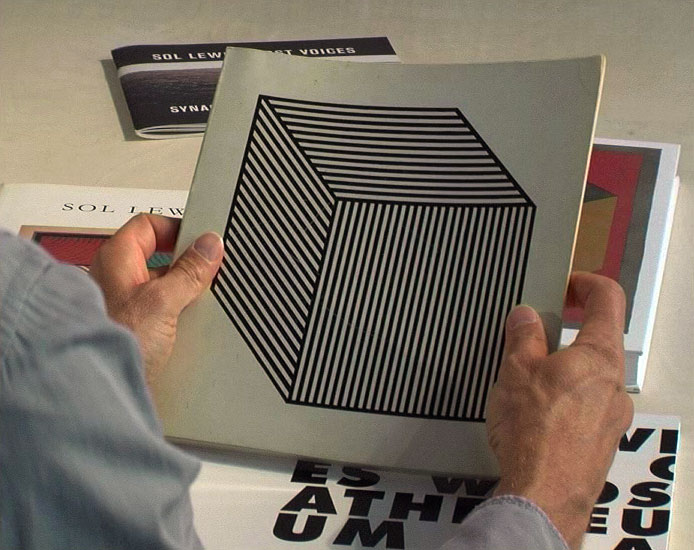

For my interviews, I pursued the strategy of first presenting the artists to be interviewed their catalogs with the request to sign them. This move also gave the cameraman time to set up the framing and the sound recording.

For this very reason, I supplemented my library at Arkana Books in Los Angeles for the individual interviews. I was aware that the husband of Bigelow’s agent ran the well-known bookstore Arkana Books in Santa Monica. Therefore, I described my film project to the owner and asked him if his partner could ask Kathryn Bigelow to meet me for an interview.

According to a precisely defined procedure that took several days I was indeed granted a telephone call with her first assistant, during which she confirmed that Bigelow found my project highly exciting, but unfortunately would be leaving for Japan the next day to film there. So, I was not lucky to meet her for an interview.

Normally, I refused to to show the interview partners the questions I intended to ask in advance. With one exception: Yoko Ono received them from me because her manager had made this a precondition for an interview. So I was full of anticipation to ask her about her motivation for her early „instruction pieces“ on the occasion of her exhibition Dream Universe at Portikus in Frankfurt (2005). Her works are historically attributed to the Fluxus movement. This was probably also the reason why Joseph Kosuth strongly criticized me during our interview for including Yoko Ono in the film and thereby treating her as a conceptual artist. I countered this criticism, however, by pointing to the conceptual precision of her „instruction pieces,“ which, because of their formulaic nature, represent ideal-typical conceptual instructions for action.

Many photographers and TV teams had come to the press conference to film or photograph the pop star Yoko Ono, even before she entered Portikus. For a long time, everyone waited for her to appear. Since she had been traumatized by the assassination of her husband, John Lennon, I expected some precautionary measures. Therefore, I was already waiting in the press room, where she finally appeared through a back entrance (the rest of the press was still waiting for her outside). In this way, she escaped the usual flurry of flashbulbs and I was able to greet her personally without being disturbed.

After the introduction by Daniel Birnbaum and some explanations by Yoko Ono, the press was given the opportunity to ask questions. But a yawning silence opened up, which in turn was filled by a flurry of flashbulbs – no one wanted to ask a question; apparently the press present was mainly interested in pictures of her. Having a long experience with press conferences as an artist and art critic, I proceeded strategically: At that moment, I asked my prepared questions, which she would not have answered in the subsequent interview. Because she had already prepared very short answers to my individual questions, some of which did not even make a complete sentence.

Already in my accompanying text to the film essay „On the Way to Conceptual Paradise“ (2005), I referred to the populism that was culturally dominant at that time. During this period, a neoliberalization of politics was pursued by the German Chancellor Gerhardt Schröder (in office until 2005). With this neoliberal political economy, the effects of which have intensified considerably up to the present under the auspices of digitalization, an economization of life in general and thus of culture has taken place, which has also reformatted the ethical values and evaluation processes in art. Although the historically first Red-Green-party government in Germany failed during the post-production of Conceptual Paradise in 2005, the commercial development described above not only lasted until the stock market crash of 2007, but continued to intensify until the current Corona crisis. A striking effect in the field of art during this time is the redefinition or even loss of art criticism, whose function increasingly became advertising or PR; this is also due to the fact that to this day art criticism is often launched by the exhibition institutions themselves – published in their own print and online magazines or in the press. Theoretical questions are often considered as too complicated. Under these conditions, I almost completely stopped writing art criticism.

I had talked with Lawrence Weiner about the political context we were in following our interview outside the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich (2004). He lamented the Christian fundamentalist political motivation of then U.S. President George W. Bush. I wonder what he would say about the current administration?

Lawrence Weiner could do little in the interview with my question about „conceptual paradigms.“ But the film title encouraged him to say: „If you speak of Conceptual Paradise – that I understand, […] that’s the use of a word in a manner that makes sense to me: There is no concept of paradise, therefore a conceptual paradise is of interest to me. When you say Conceptual art – no. The stuff I make is real, turn off the lights, in the old words of Ad Reinhardt, you can trip over it. You can fuck up your life – that’s not very conceptual, it’s a material reality.“

How did the title of the film essay come about? During the rough cut, Viola Klein, who edited the pre-cut, asked me why the interviewees kept talking about the „Conceptual Paradise“ and what it was all about? As interesting as I found her misunderstanding of „conceptual paradigms,“ I liked the sound and meaning of the two words. At that moment it was clear to me that the project had been given a new title: Conceptual Paradise.

Shilpa Gupta resisted the term conceptual art: „As an Asian artist it’s even worse, because there is a certain hierarchy which is always built-in, as to say, hey, you’ve copied from the West, or hey, you‘ve picked up. And it’s sort of, that this sentence is not for inquiry, but to create a level to say that you have been influenced and therefore you are not so good.“

Along the same lines, Renée Green says, „The notion of a conceptual paradigm was always a problematic one, and it’s one that was refused by different of the people that have been labelled as conceptual.“

Harun Farocki asked me in a telephone conversation what was hidden under the water lilies that I use as an iconic image for the overall project Conceptual Paradise. And he wasn’t satisfied with me referring to a film take in the ‘Flora’ (botanical garden) in Cologne for the clip about Marcel Broodthaers. He couldn’t do anything with it because he lacked the contextual information that Broodthaers had critically dealt with the form of the exoticizing winter garden as a representative framing system of art and that the practices of Renée Green and Mark Dion, for example, partly refer to it. Thus, in the Cologne ‘Flora’, plants are sorted by nation, which follows the identity-fixated taxonomy. According to Carl von Linné, it associates plant and animal origins with national territory and ownership. With his exhibition „The Eagle in the Oligocene“ Broodthaers had also problematized iconography as an ordering system in art history. In a radical reading, it could even made responsible for stereotyping racism. My exhibition on the subject of exoticism, „Mixed Up Images,“ Cologne 1997, which I had conceived as an urban research project, was oriented on this.

I chose the photograph with the water lilies as an iconic image for my project on conceptualism because it simultaneously embodies a symptomatic paradox: The beautiful flower feeds off the murky silt. It seems exotic, it inspired ornamentation, and it is distinguished from the lotus flower. Moreover, the lotus flower, which also thrives in the water, stands in the Buddhist system – shortened – for the infinitely unfolding spirit. Thus, the water lily image unites a critique of science with a mystical conception. I consider this to be an ultimate image metaphor of a project image.

On the last day of shooting in Los Angeles, we only have one interview with Charles Ray. We have trouble finding his house, because the suburban homes in this neighborhood are very similar and mostly don’t have house numbers. Finally, I’m pretty sure I’ve found Ray’s house, because one bungalow stands out from the uniformity of the residential neighborhood: not only is it heavily overgrown with the Morning Glory bindweed but two large painted eyes stand out from it on the roof. At first, Katja doesn’t want to believe that this hippy attitude adorns Ray’s house. We approach the entrance and find his name on the sign.

Charles Ray opens the door for us with a bicycle helmet on his head and asks us to wait a moment. Through the door, which is opened only partly, we are presented with a bizarre picture: In the living room, he walks up and down for about ten minutes, talking into a very large house phone that appears to be from the 1980s. The image seems absurd to us. It apperars to be deliberately staged, and I finally ask the cameraman to record this scene.

But suddenly Charles Ray steps out of the front door and angrily asks us to stop our recording immediately, because he had not given his consent to record him in this private situation. We immediately delete the recording. But he is agitated and wants to postpone the planned interview until the next day. This is not possible for us because our return flight is booked for the next day. Thus, we also have to do without his voice about conceptualism.

(Translation Stefan Römer)